We Cannot Thrive Alone

The WHO Commission on Social Connection urges bold leadership—because disconnection isn’t peripheral, it’s profound.

She wasn’t lonely because no one was around.

She was lonely because no one noticed. Because no one asked how she’d been sleeping, or remembered her story from last week. Because she hadn’t felt anticipated in a very long time.

Loneliness has caught the attention of an increasing number of governments in recent years. It’s often described as a public health crisis—but that framing can miss something quieter, more elemental: that what we truly long for is to be witnessed, not just included. Its scale and urgency were formally recognised at the World Health Assembly in May 2025, with the adoption of the first-ever resolution on social connection—affirming that social connection is vital to public health and calling for coordinated action.

This piece explores a different way of thinking about loneliness and connection. Not as a deficit to be solved, but as a universal human need—for resonance, for recognition. A need that is often met not through systems or scale, but through small, sacred gestures.

Witnessing Matters: What the WHO Report Teaches Us About Connection

This is not a summary of the WHO Commission on Social Connection report, From Loneliness to Social Connection – Charting a Path to Healthier Societies, launched on 30 June—but it is written in homage.

To the Commission, the team of experts at WHO, every contributor, and every person reading it.

Their work matters.

The launch event—which can be revisited—was a remarkable 90 minutes that spoke not only to me personally, but to anyone watching as a member of a local, national, or global community.

In those few moments, we were all the same—regardless of gender, socio-economic status, race, or age.

Each Commissioner shared their personal reflections on loneliness. When have we ever seen that? They gave each of us permission to recognise our own experiences—not as personal failings, but as deeply human truths.

The WHO Commission report is not a campaign pitch.

It is a reference document of substance.

Meticulous and far-reaching, it’s designed not only to inform—but to be used.

For those of us working in policy, care, or community action, it offers more than affirmation.

It offers a roadmap.

At nearly 300 pages, it is rigorous and deeply human—a document that finally gives weight to what many of us have long known: that social connection is not a luxury.

It is essential to survival.

The evidence is clear.

The recommendations are precise.

And the examples span geographies and sectors—making this a document we should return to again and again.

Not just to cite, but to guide how we design, fund, and imagine what meaningful connection can look like across the life course.

Because loneliness and isolation aren’t just unpleasant—they are dangerous.

And connection isn’t just nice—it’s life-saving.

The Case for Connection: What the Report Makes Clear

The report begins by clarifying something too often misunderstood: social connection is not simply the presence of people in our lives. It encompasses the structure of our relationships—how often and with whom we interact—their function, in terms of support and reciprocity—and their emotional quality.

It also distinguishes between loneliness—the subjective feeling of being alone—and social isolation, the more objective absence of social contact. Both are harmful. Both are patterned by inequity and exclusion. Yet they are not the same, and they require different responses.

What makes the Commission’s work so powerful is not only its moral clarity, but the strength of the evidence it presents.

Loneliness is now recognised as a serious health threat, increasing the risk of heart disease, stroke, dementia, anxiety, depression, poor immune function, and premature death. The risks are comparable to smoking 15 cigarettes a day—and greater, even, than those associated with obesity.

These are not soft findings.

They are clinically significant, system-wide, and disproportionately impact those already most at risk—older adults, caregivers, migrants, people living with disability, and those facing poverty, marginalisation, or grief.

The report makes one thing clear: we are not dealing with a fringe issue. One in four older adults globally report being socially isolated, and up to one in three experience persistent loneliness.

But this is not limited to ageing populations. Young people, too, are experiencing disconnection in growing numbers—shaped by economic instability, digital fragmentation, and the erosion of traditional community structures.

In many countries, the shift toward individualism, urbanisation, and weakened public space has hollowed out the places and rituals that once helped people feel seen.

What Makes Connection Work: Real-World Interventions That Resonate

And yet, there is hope in the Commission’s vision.

The report details promising strategies that have already shown impact around the world—from social prescribing initiatives that connect patients with community-based activities, to peer support networks that reduce risk through mutual care. It points to cities where urban design has been reimagined to invite conversation and encounter, and to programs that foster intergenerational connection, cultural belonging, and meaningful participation.

These are not stopgap measures. They are interventions that recognise the opposite of loneliness isn’t simply company—it’s resonance. It’s being witnessed.

Social Prescribing Initiatives – These programs, especially prevalent in the UK, enable health professionals to refer individuals to non-clinical services such as community groups, arts, volunteering, or physical activity. The report highlights these as effective in reducing loneliness and improving wellbeing by linking people to community assets and opportunities for meaningful engagement .

Loneliness Awareness Campaigns – Initiatives like Loneliness Awareness Week in Australia, the USA, and Japan have successfully raised public awareness, encouraged open dialogue, and engaged governments. These campaigns use storytelling, media engagement, and national coordination to normalize conversations around loneliness and drive systemic action .

Built Environment and Urban Design Strategies – The report cites city-level innovations that redesign public spaces to foster interaction and connection. This includes efforts to enhance accessibility, create inclusive community hubs, and design environments that invite spontaneous social encounters—especially benefiting older adults and those with mobility limitations.

From Research to Resonance: Why Stories Matter

The WHO Commission report opens not with statistics, but with stories. Testimonies from David in New Zealand, Macy in Zimbabwe, and Julio in Costa Rica remind us that loneliness is not an abstract concept—it is lived, felt, and carried. David speaks to the healing power of peer support and the slow rebuilding of a social identity. Macy names the ache of not feeling understood. Julio reflects on love, loss, and the quiet withdrawal that can follow.

These grounded narratives do more than illustrate the problem—they dignify the human experience behind the data, and they anchor the report’s findings in voices too often left out. They remind us why this work matters.

If you do nothing else today, take the time to watch their stories. Let them be seen, and let David, Macy, Julio and many others in the Report who are brave, courageous and insightful.

David’s Story (New Zealand) – “I would say that the answer to unhappiness is connection, to groups, activities, to nature, to things and people that give us a sense of fulfilment and reward. I believe in the power of peer support, drawing on the lived experience of people who have found a new sense of self, who have reimagined a social identity and brought [it] into being.”

Macy’s Story (South Africa) – “When I think about loneliness, I think about not having a person to depend on. I always feel isolated because I don’t think I have people that understand me.”

Julio (Costa Rica) – “At one time, I had a boyfriend, I had a partner, I built a home. He passed away, I became a widower. If I had known years ago that I would reach this age and it would lead to me withdrawing from civil society, maybe I would have prepared myself psychologically for how to embrace old age.”

Each story is a reminder that small, intentional actions—especially when sustained—can be transformative.

What is your small intentional action?

Connection as a Public Health Mandate: The PRIME Agenda

The WHO Commission doesn’t stop at diagnosis.

It sets out a five-part agenda for global action—captured in the acronym PRIME. It calls on governments and stakeholders to:

Prioritize social connection as a public health imperative

Reinforce social infrastructure through proven programs

Invest in research and data to understand what works

Mobilize cross-sector partnerships for collective impact

Elevate lived experience to shift public mindsets

At the heart of these recommendations is a simple, radical idea: connection is a right, not a reward. Systems must be designed to support it—not as a luxury or afterthought, but as fundamental to human wellbeing.

For those of us working in ageing, this is the most comprehensive mandate we’ve had in years.

The Commission gives form and force to what older people, families, carers, and communities have long said quietly—or endured alone. It offers language, evidence, and urgency.

But it also does more than affirm our concerns. It challenges us to act—to confront the conditions that create and deepen disconnection, and to build systems of care, infrastructure, and imagination rooted not only in need, but in our shared humanity

How what we track matters

While the WHO Commission offers one of the most comprehensive explorations of social connection to date, it does not pretend to have all the answers. The report is candid about its own limitations—especially the gaps in global data, the uneven inclusion of age groups, and the need for better tools to measure what connection and disconnection truly mean across cultures and lifespans. Its estimates of harm are grounded in strong evidence, yet they still rely on generalizations that don’t fully reflect the complexity of lived experience.

Rather than diminishing its value, these acknowledgements underscore what’s needed next: deeper investment in research, more inclusive surveillance, and a commitment to refining how we track what matters.

One striking absence in the Commission’s otherwise sweeping report is a serious engagement with loneliness in long-term care. While older adults are rightly identified as a high-risk group, the report does not overlook them—but it lacks the data to account for those living in residential or institutional settings, where isolation can be most profound and persistent.

For anyone who has worked in or visited aged care homes, this gap is glaring. If we are to fulfil the promise of social connection as a public health priority, we must do more than reach people in their communities. We must also reimagine the culture of care inside institutions—places that too often strip away relationships, resonance, and meaning.

A Different Kind of Call to Action: Seeing, Knowing, Showing Up

We often treat loneliness as a public issue that can be addressed through structure, strategy, and service delivery. But the invitation from this report is something more human: to consider the emotional reality of what it means to feel connected.

Sometimes what makes a difference is not a new program, but something more human:

Remembering a story someone shared weeks ago.

Establishing a simple ritual with a neighbour or friend.

Using someone’s name when you greet them.

Showing up, especially when it would be easier not to.

The opposite of loneliness may not be friendship, intimacy, or formal support networks.

It may be the reliable sense of being noticed.

Of being missed.

Of being known.

That’s where connection begins.

And this is not soft. It’s the foundation of being human.

It’s about recognising that emotional vulnerability is not a weakness—it’s a shared condition, and one that systems, communities, and individuals must take seriously if we are to build healthier, more connected societies

###

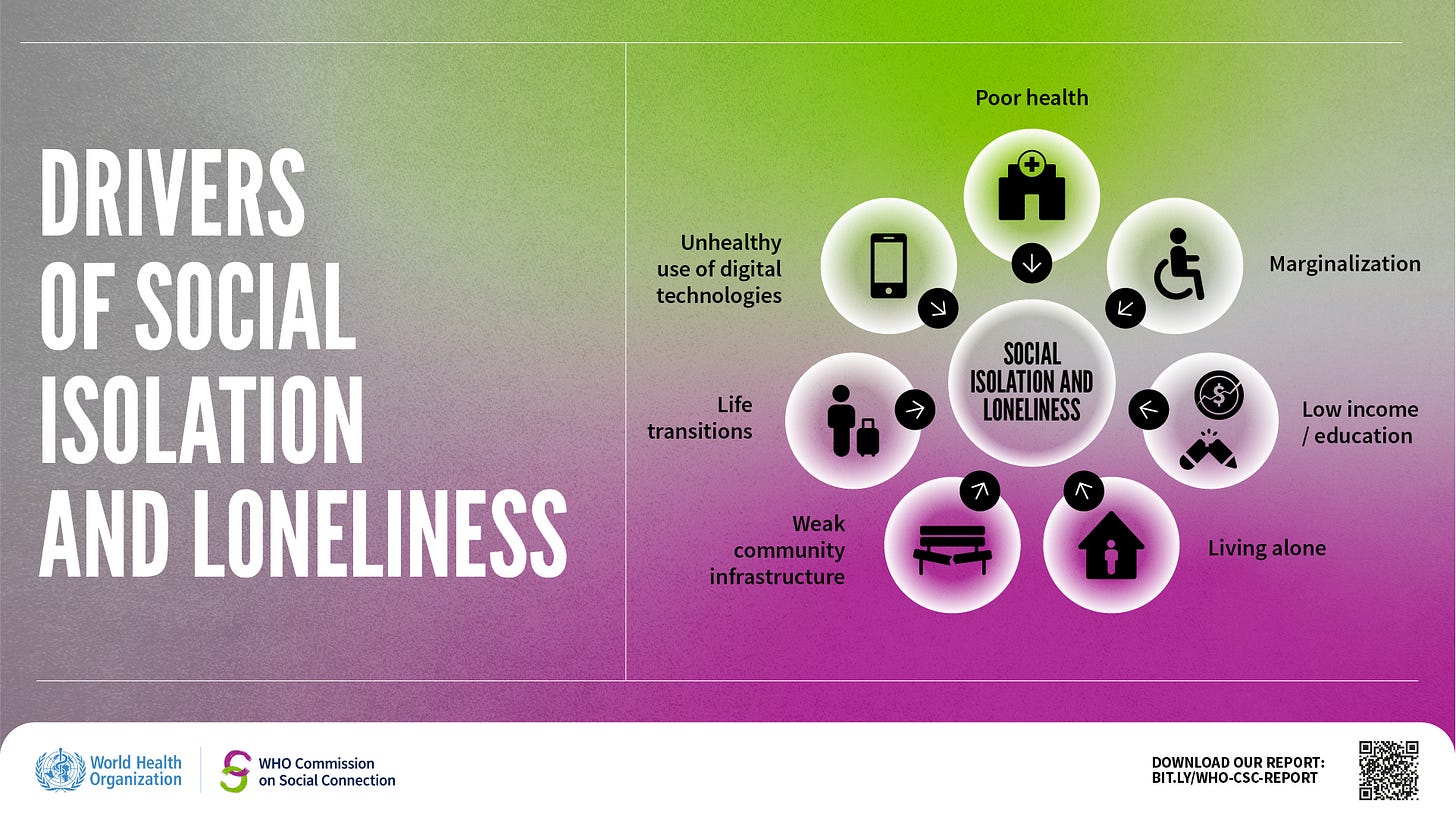

To explore the full WHO Commission report, access supporting PowerPoint slides, and download shareable infographics, please visit the official website of the WHO Commission on Social Connection. These tools are designed to inform your work, strengthen your advocacy, and help bring the power of connection into practice.

References

From loneliness to social connection - charting a path to healthier societies: report of the WHO Commission on Social Connection. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2025. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://www.who.int/groups/commission-on-social-connection/report

This spoke to me loudly at many levels. Of working in disability... and finding the answer to each question in the local community, where connections would sustain.

On a personal level — of my concerns about my mother following my father's death. She was rarely alone, but often lonely.

And as a final thought — how will I fare, I wonder, if I live well into my 90s or beyond? What if my friends don't live that long? I need my own version of PRIME to build in the safeguards now.